Faith & Worship

Faith & Worship It might

be assumed that worship in the early Christian Church was fairly spontaneous,

used as we are to seeing perhaps the occasional poetic prayer attributed

to St Patrick or his contemporaries. We might also think that set orders

of service are a relatively modern introduction. Actually, this is not

the case, certainly for congregational acts of worship.

It might

be assumed that worship in the early Christian Church was fairly spontaneous,

used as we are to seeing perhaps the occasional poetic prayer attributed

to St Patrick or his contemporaries. We might also think that set orders

of service are a relatively modern introduction. Actually, this is not

the case, certainly for congregational acts of worship.By the fourth century the Church was praying together more often than

individually and along with the prayers are found psalms and hymns. Psalms

148-150 are associated with morning prayers each day in the week and Psalm

141 in the evening.

A division of sorts is suggested between what is often called the ‘cathedral’

style of daily office upon which Catholic and Protestant churches still

use today and that of the ‘monastic’ pattern of worship developed

in the fourth century, as there are differences not only in the external

form of worship but also on the spiritual emphasis of both.

The Lord bless you and keep you.

May He show His face to you and have mercy.

May He turn His countenance to you and give you peace.

The Lord bless you!

(A prayer of St. Francis)

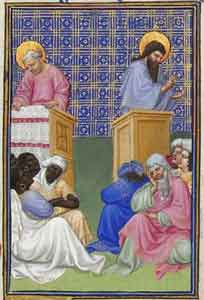

We have considered in the previous study the Christians who made their

home in desert places and led an austere and monastic life. At the heart

of monasticism was separation - surrendering of earthly riches and temptation

and entering into a community of meditation and prayer.

Those who had committed their lives to one of monastic solitude in desert

or wilderness places tended to favour a pattern of prayer which followed

the Apostolic call in 1 Thess. 5:17 to ‘Pray without ceasing.’

And they took this literally, stopping only for the briefest time to sleep

and eat. They prayed while the worked and worked while they prayed, from

dawn until nighttimes, whether involved in daily chores such as milking

cows, preparing meals, or tending crops. Columba had the reputation he

would not spend one hour without including study, prayer or writing.

There is an apocryphal tale of Saint Cuthbert and some of his companions

shipwrecked on an uninhabited beach. Beginning to fade of hunger, Cuthbert

encouraged his companions to pray, saying “Let us storm heaven with

prayers!” Soon after this they came across 3 cuts of dolphin meat,

looking like they had been prepared by human hands, which they ate.

In their prayers Christians reflected on the mighty works of God and prayed

for spiritual growth and personal salvation. They prayed using the Psalms,

particularly when praying together. Listen to the words of St Patrick,

whose background was in the monastic movement.

“I prayed frequently during the day. The love of God and the fear

of Him increased more and more and faith became stronger and the Spirit

was stirred, the Spirit was then fervent within me.”

Within the monastic communities rules of life were developed, such as

that of the fifth century St. Benedict.

Traditionally, the daily life of the Benedictine revolved around the eight

canonical hours. The monastic timetable or Horarium would begin at midnight

with the service, or "office", of Matins (today also called

the Office of Readings), followed by the morning office of Lauds at 3am.

Before the advent of wax candles in the 14th century, this office was

said in the dark or with minimal lighting; and monks were expected to

memorise everything.

These services could be very long, sometimes lasting till dawn, but usually

consisted of a chant, three antiphons, three psalms, and three lessons,

along with celebrations of any local saints' days. Afterwards the monks

would retire for a few hours of sleep and then rise at 6am to wash and

attend the office of Prime. They then gathered in Chapter to receive instructions

for the day and to attend to any judicial business.

Then came private Mass or spiritual reading or work until 9am when the

office of Terce was said, and then High Mass. At noon came the office

of Sext and the midday meal. After a brief period of communal recreation,

the monk could retire to rest until the office of None at 3pm. This was

followed by farming and housekeeping work until after twilight, the evening

prayer of Vespers at 6pm, then the night prayer of Compline at 9pm, and

off to blessed bed before beginning the cycle again.

Those who belong

to mainstream denominations may be used to following a weekly pattern

of liturgy comprising at the very least of morning and evening prayer

and the celebration of Holy Communion, and be familiar with the repetition

of prayers, some of which we know have their roots in the 1662 Book of

Common Prayer. But as has been mentioned above, forms of Christian liturgy

have been around since the early days of the church.

Those who belong

to mainstream denominations may be used to following a weekly pattern

of liturgy comprising at the very least of morning and evening prayer

and the celebration of Holy Communion, and be familiar with the repetition

of prayers, some of which we know have their roots in the 1662 Book of

Common Prayer. But as has been mentioned above, forms of Christian liturgy

have been around since the early days of the church.

At Iona in the time of St Columba, Mass was said on Sundays and feast

days, but by the 7th century we hear of priests celebrating twice on the

same day.

The Bangor Antiphonary, a seventh century manuscript which is now preserved

in the Ambrosian Library, Milan contains, among others three Canticles

from the Bible; the Te Deum, Benedicitie, Gloria in Excelsis; ten metrical

hymn ; sixty-nine collects; seventeen special collects; seventy ' anthems'

or versicles, an unusual form of the Creed, the Lord's Prayer.

The Book of Mulling is an Irish pocket Gospel Book from the late 8th century.

The text collection includes the four Gospels, a liturgical service which

includes the Apostles' Creed.

There are others, including the Stowe Missal from the eighth or early

ninth century containing variations of liturgy for the Mass, Baptism and

Visitation of the Sick, and which contains non-Roman elements.

The Book of Cerne is a large early ninth-century manuscript collection

of prayers, etc. made for Æthelwold, Bishop of Lichfield (820-40).

It once belonged to the Abbey of Cerne in Dorset, but is Mercian in origin

and shows Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, Carolingian, Roman, and Byzantine influences.

These were not liturgies that could be undertaken within the space of

an hour, in medieval Christianity it took up much of the day!

As you might have noticed, there seems to be the influence of Rome on

the liturgy of the Church at this time, albeit with a local flavour. This

is because the Church in the West generally had at its core an adherence

to Rome and the Pope.

It is a little bit hazy as to the date when Christianity first made it

to Roman Britain. The earliest support for the idea that Christianity

arrived in Britain early is Quintus Septimus Florens Terullianus also

known simply as Tertullian (AD 155-222) who wrote in "Adversus Judaeos"

that Britain had already received and accepted the Gospel in his lifetime.

We know that in the year 314 three bishops from Britain were present

at a council held at Arles in the south of France. During the rest of

this century bishops from Britain were present at other ecclesiastical

councils, showing that the British Church was in no way isolated but was

in active communion with the rest of the Church in the Empire.

As Anglo-Saxon raids were increasing in England, Ireland was being evangelized

by Bishop Palladius, sent by Pope Celestine I in AD431-2 and a Romano-British

Christian called Patrick.

Augustine was the prior of a monastery in Rome when Pope Gregory the Great

chose him in 595 to lead a mission, usually known as the Gregorian mission,

to Britain to convert the pagan King Æthelberht of the Kingdom of

Kent to Christianity.

Æthelberht converted and allowed the missionaries to preach freely,

giving them land to found a monastery outside Canterbury city walls. Roman

bishops were established at London and Rochester in 604, and a school

was founded to train Anglo-Saxon priests and missionaries.

As a result of this contact with the rule of Rome and the missionary zeal

of the Roman Church, worship in Britain and Ireland was always going to

be influenced in style, organisation and pattern of prayer by that tradition.

is an early form of liturgy used in the West, originating in Jerusalem,

established in Gaul in the 5th Century and known in Ireland, mixed with

Celtic customs. The known elements are listed below – compare it

with the liturgy that you are familiar with today:

- Introit

- The Ajus (agios) sung in Greek and Latin. Following this, three boys

sing Kyrie Eleison three times. Followed by the Benedictus.

- Collect Old Testament reading

- Epistle or Life of the Saint of the Day

- The Benedicite and Ajus (agios) in Latin

- Gospel reading

- Sermon

- Dismissal of catechumens (baptismal candidates)

- Intercessions

- Great Entrance and the Offertory chant

- Kiss of Peace

- Sursum Corda, Preface, Sanctus, and Post-Sanctus Prayer

- Roman (Gregorian) Eucharistic

- The Fraction (the host is divided into nine pieces, seven of which are

then arranged into the shape of a cross)

- Our Father

- Blessing of the People

- Communion of the People

- Post-Communion Prayer

The Celts were great collectors of books and knowledge. Their love of

poetry and liturgy led them to add their own touches to the pattern which

originated in Rome, but it is more in the area of private prayer and poetry

that we see the real originality of Celtic thought.

Throughout the Scriptures we find the Psalms quoted, so it is quite understandable

that the early Church should use them as part of their worship, perhaps

a lot more so than we do today.

Ephesians 5:19 talks about believers ‘addressing one another in

psalms and hymns and spiritual songs...’

One of the earliest records of the Psalms being used as part of Christian

worship comes from a fourth-century pilgrim Egeria who reports that on

Good Friday in Jerusalem the readings ‘were all about the things

that Jesus suffered: first the psalms on this subject, then the Apostles

which concern it, then passages from the Gospels. Then they read the prophecies

about what the Lord would suffer, and the Gospels about what he did suffer.’

It was with the Desert Fathers and the early monastic communities that

psalms began to be used regularly within daily worship. They encouraged

their followers to memorise the entire contents of the book and recite

it during their waking hours. Some would spend the whole night simply

reciting the psalms from memory.

The practice was to use the psalms as an inspiration for silent prayer

and meditation. A psalm would be read, followed by a time of silence,

and this pattern repeated. Why such an emphasis on the psalms? Possibly

because the Scriptures see prophesies relating to the Messiah within them.

The fact that the psalms were written in a way that made the singing of

them possible was seen as God’s way of making learning more fun!

The fact that some psalms are more cries of desperation or anger than

songs of praise did not deter them – it was the act of saying or

singing them that was pleasing to God!

Over many generations the periods of silence between the singing of psalms

grew shorter and shorter. An early monastic Rule of the Master says that

this is to avoid the risk of anyone falling asleep or being tempted by

evil thoughts!

Within the more formal ‘cathedral’ services the psalms were

used as ‘hymns’ with a verse sung by a member of the clergy

and the congregation repeating a refrain. Psalms such as 51 (‘Have

mercy on me, O God...’) start appearing at the start of services

as a act of penance. Psalm 116 was used at funeral services as the body

was prepared for burial.

References:

Bradshaw, Paul F (2009). Reconstructing Early Christian Worship. SPCK

Lizzi Langel, Celtic Christian Principles for a Modern Day Monastic Community, Field Assignment for SBCW , University of the Nations 2006

Mitton, Michael (1995). Restoring the Woven Cord:

Strands of Celtic Christianity for the Church Today, Darton, Longman

& Todd.

©John Birch · Prayers written by the author may be copied freely for worship. If reproduced elsewhere please acknowledge author/website

Privacy Policy · Links · Author · Donate